The great furniture, lighting and interior designer of the early 20th century, Jean-Michel Frank, was first revealed to me by a friend in America. We were in a book shop in San Francisco in 2001 and he said; “You have to get this book. It will change your life.” Those words were to prove truer than either of us would have expected at the time.

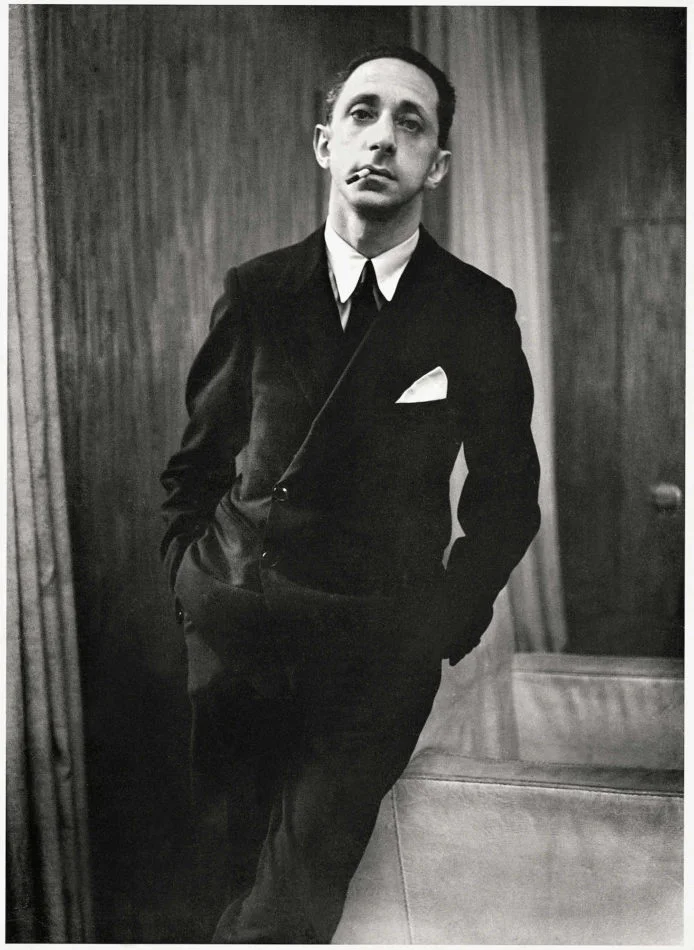

Later on I sat with the book and slowly turned the pages. Pictures of a thin, shy-looking man in dapper clothes were followed by images of austere rooms with shiny walls and simple furniture. My first impression was a feeling of emptiness within the spaces. But as I looked carefully, within the emptiness I found objects, furniture, lighting and surfaces that were captivating, beautifully balanced and texturally delightful. I have since spent many moments of the last 21 years warmed and encouraged by those images. I am lucky to have experienced none of the tragedy that Frank lived, but I feel a connection to him through ideas of beauty and soulful authenticity.

Born in Paris in 1895 with parents who were German Jews, Frank’s brothers both died in 1915 fighting for France while his parents were placed under house arrest. Later that same year, under terrible stress and having had his assets seized by the French government due to his German nationality, his father Léon committed suicide. His mother Nanette had severe depression for many years and died in an asylum in 1928. Jean-Michel himself finally left France in 1939 after his years of success, to escape the Nazis. Frank had depression and physical health problems for much of his life, and an addiction to opium until his death at the age of 46 in New York from an overdose.

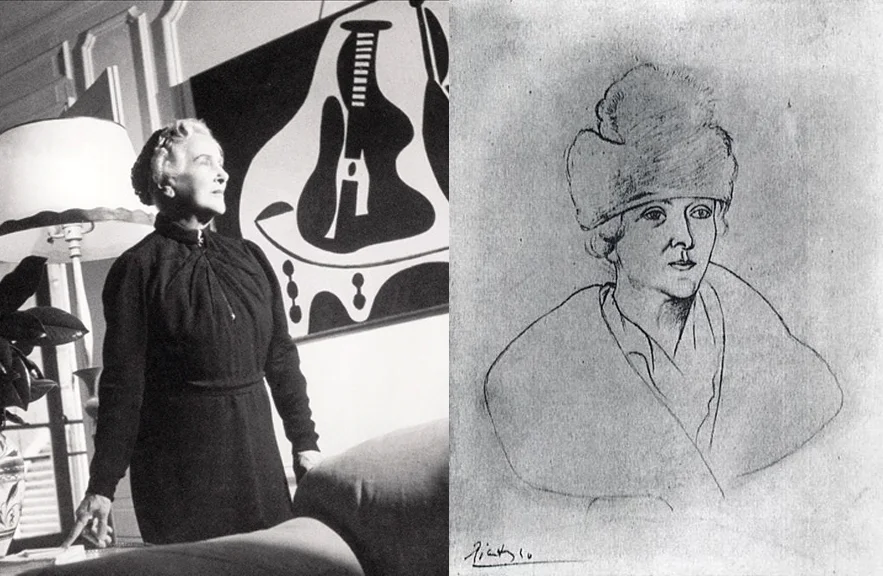

Pierre-Manuel Martin-Vivier in his major work ‘Jean-Michel Frank: L’étrange luxe du rien’ (The Strange Luxury of Nothingness) interviewed people who remembered Frank as ‘thin, short, nervous, intense and usually dressed in grey suits – except at balls where he would often go wearing white ball gowns.’ An old classmate, Jacques Porel, in his 1951 memoirs ‘Fils du Réjane’ (son of Réjane – his famous actress mother) described Frank as ‘a sort of child-woman, ageless and sexless… with oriental doll looks and a falsetto voice.” He was teased mercilessly at school for being weak and effeminate and the son of German Jews.

Despite this catalogue of traumatic events and difficulties, Frank went on to make a profound, prolific and enlightened impact on the design of interiors and furniture – an impact still felt strongly today.

What was it that oriented Frank away from his original seemingly assigned career in the law to become, with no design training, one of the great designers of the twentieth century? He clearly discovered a love for the good life, having later inherited family wealth. He travelled to the French Riviera, Spain and Italy, usually in the company of artistic celebrities. So we can imagine the creative life luring him with its theatre and panache.

During decades working with the same techniques and materials that Frank loved, I have discovered that design can bring the joyful escapism of ‘play’. I imagine that for Frank the world of craftsmanship, with its skills, characters and structures, and the application of exceptional natural materials, in all their vulnerable, iridescent depth, might have brought a pure, simple and invigorating energy to his wondering, sometimes troubled mind. The making of beautiful things, although full of its own creative frustration and technical challenges, can be deeply nurturing and refreshing as ideas and later objects come forth.

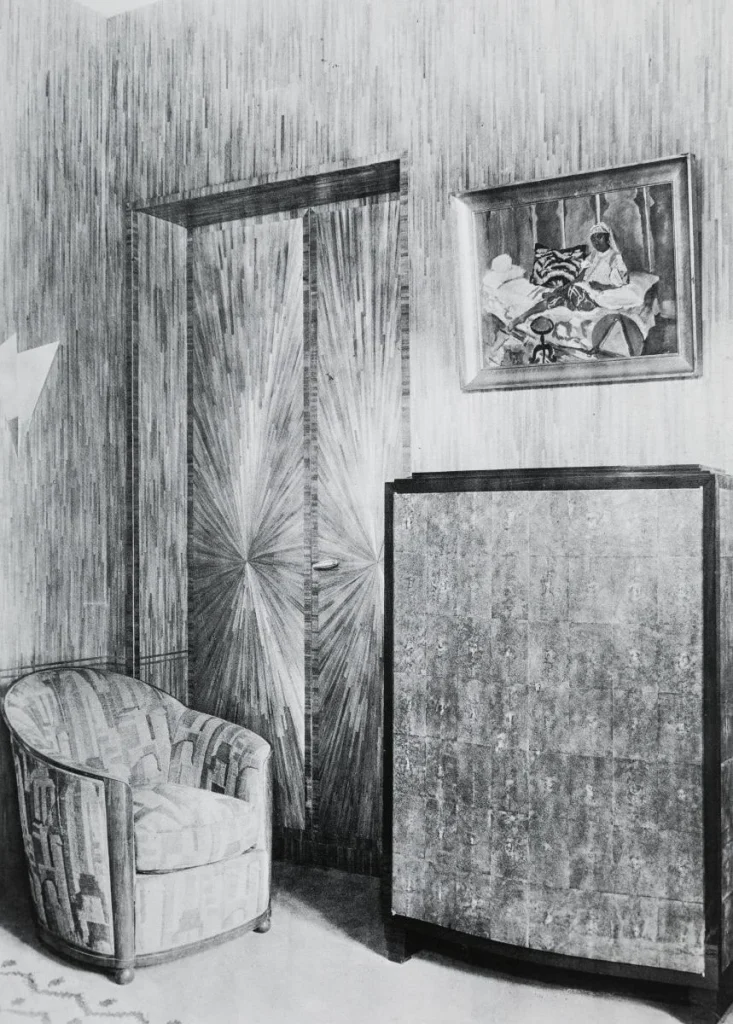

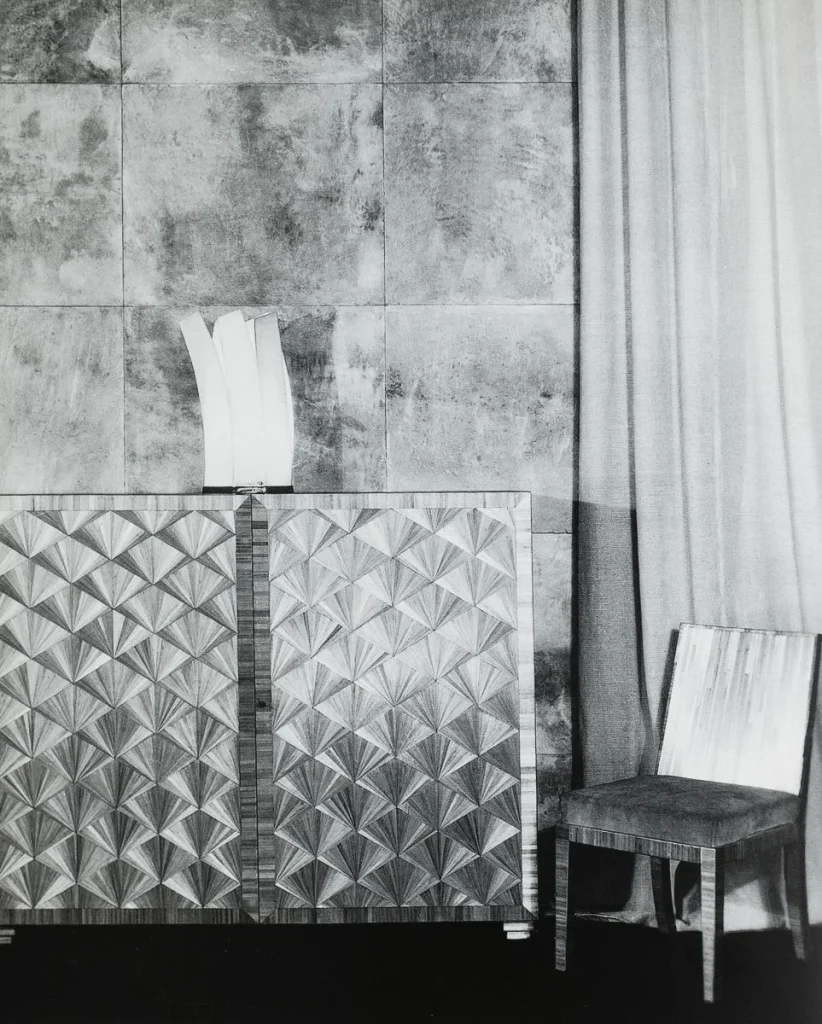

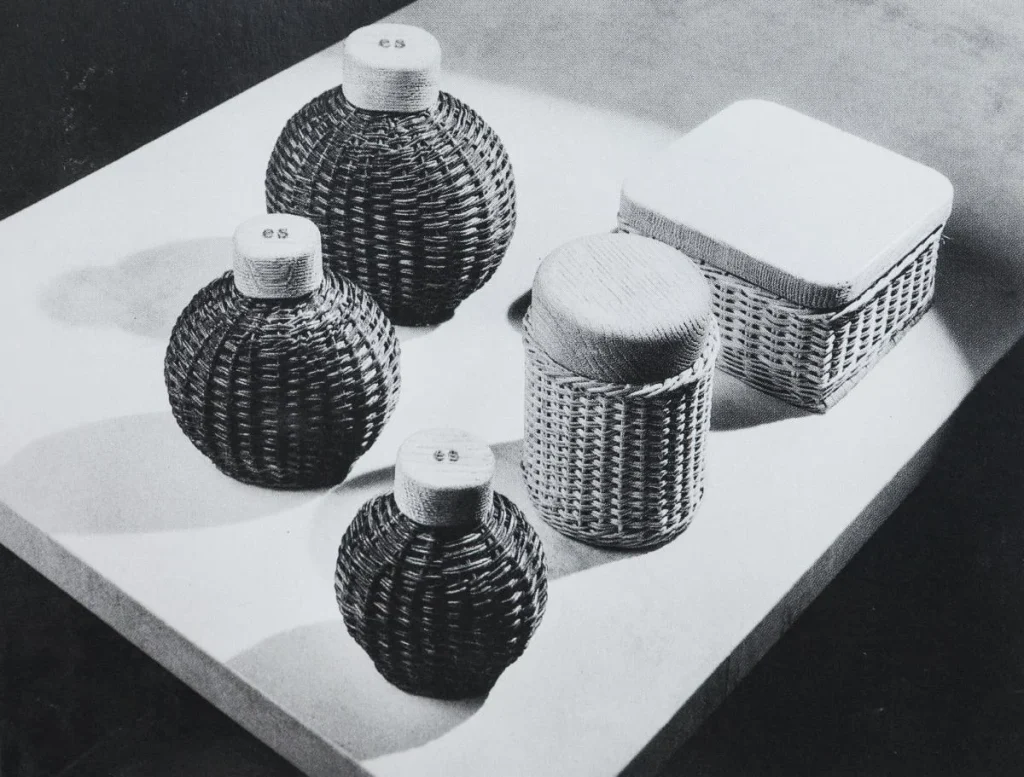

Shagreen is one of the materials that Jean-Michel Frank is famous for ‘bringing into the light’; using it on furniture, lighting and accessories. Although it had been used in complex decorative, scientific and military works from the 15th century in Asia and 18th and 19th centuries in Europe, he saw its beauty in broad oblongs of ivory or chocolate tones – the subtle natural variations bringing a sense of rawness coupled with luxury when applied to simple structures. How did he become acquainted with shagreen in the first place? Possibly it was after he met the Russian artisan who produced Frank’s shagreen pieces in Paris? I like to think that the material itself reached out to him. ‘What is that material made up of tiny ivory beads? Where on earth does it come from? How can I find out more about it?’ This excitement at a still, polished surface, can be every bit as electrifying as a painting on a wall. More so for the sensualist who loves to feel textures on the skin or enjoy things aglow in the light of candles. Textured natural materials of noble and ancient renown were to fill all of Franks interiors.

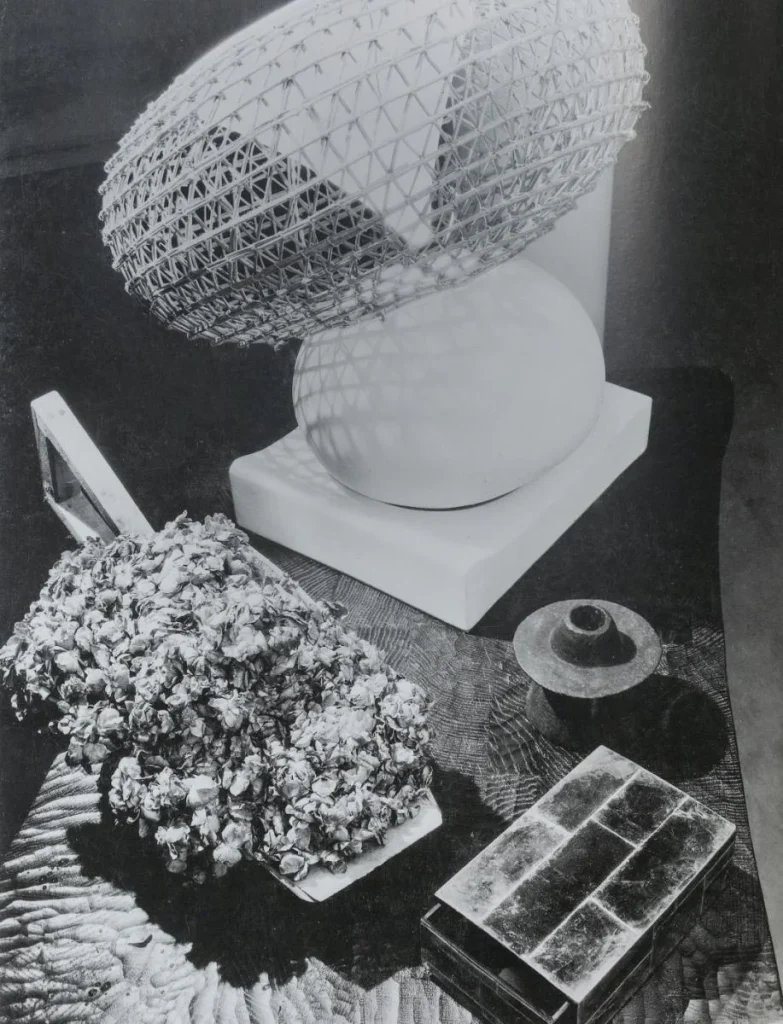

To return to the people that surrounded him as he explored Paris in his early days, great designers and artists are always encouraged and pushed to new heights by their patrons and admirers. It is their reaction to the people and ideas they encounter that provides energy for their passions. Frank met Eugenia Erraźuriz in around 1926. She was a famous, beautiful Chilean woman, 35 years his senior (you can read an article on her in our blog) and she became a friend and mentor to Jean-Michel. It is quite probably her own strong minimal and modern aesthetic that opened Frank’s eyes to this style; a sense of a new simplicity that refreshed and excited him. His connection with Erraźuriz and other artists of the beau monde led to beautiful design collaborations with Salvador Dali, Christian Bérard, Alberto Giacometti and Emilio Terry. Frank was a pioneer in incorporating the ideas of other designers into his own ‘brand’. His aesthetic also allowed for strong concurrent designs – minimal alongside floral; smooth alongside sculpted. The diverse forms were harmonized through the extremely high calibre of the craftsmanship and the materials. Ivory shagreen tables could live beside dark textured bronze lamps and white plaster shell sconces; ivory parchment beside glimmering amber mica panels and black obsidian lamps. The individual parts were each a small world of natural resonance that brought vitality and depth.

Frank also drew from the same cultural sources that were having such a potent union with the modern master painters of his age. African, Chinese and Egyptian forms were harnessed and re-imagined through the eyes of the reductionist visionary. As Martin-Vivier writes he ‘played with the codes of design and reduced styles to shadows, essences.’

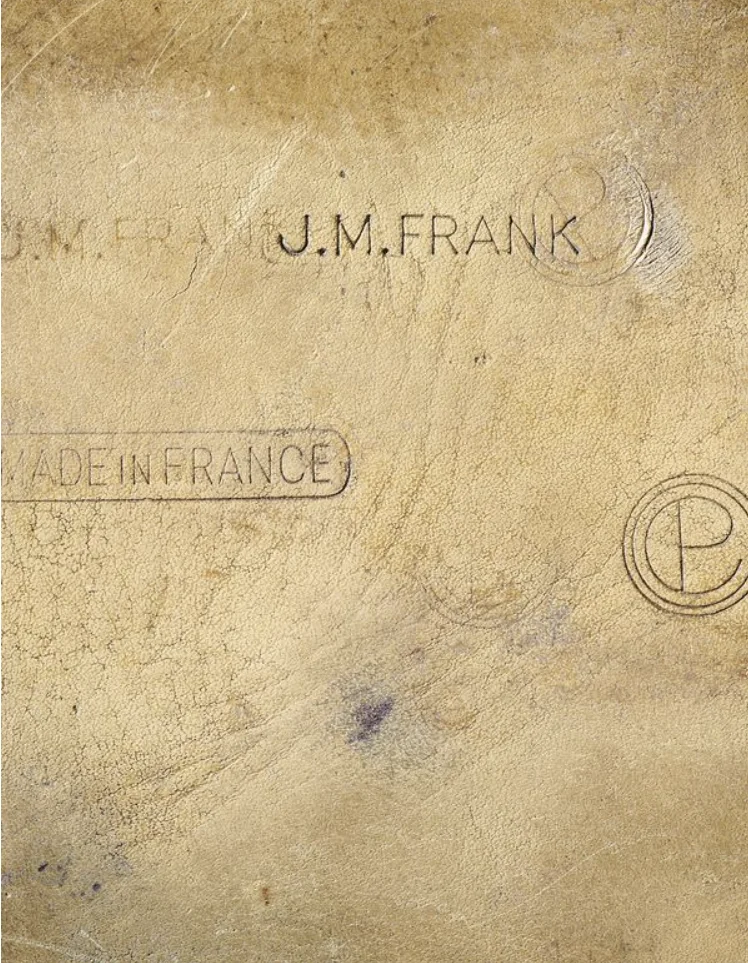

Another important man in Frank’s life was the cabinet-maker Adolphe Chanaux. By partnering in business with Chanaux, Frank was able to execute and deliver the interior projects and furniture for which he was increasingly in demand. Shagreen, parchment, mica and straw all need a structure to become an object and Chanaux provided simple, quality structures. He also managed the production and deliveries that were not Frank’s focus, and ensured a solid success behind Frank’s ideas.

I have learned through my own experience of the importance of this very special partnership between designer and workshop. The workshop, for the designer, is a liberating place. Building such an organization is like planting the fields in expectation of great harvests to come: it takes time and patience and a profound respect for the natural materials that we work with. Walking through our workshops today, surrounded by people I have known for years, rich in skills and patience, is a great inspiration for future designs. Every day there is a hint of something new and emerging. Accidents and mistakes lead to new ideas. The workshop is a laboratory that brings forth evolving ideas and fusions. I have found that it is only within one’s own workshop that you can reach the endpoint of a design; refine the skills, details and processes until it is just right, and that is even more true when using unusual and difficult materials.

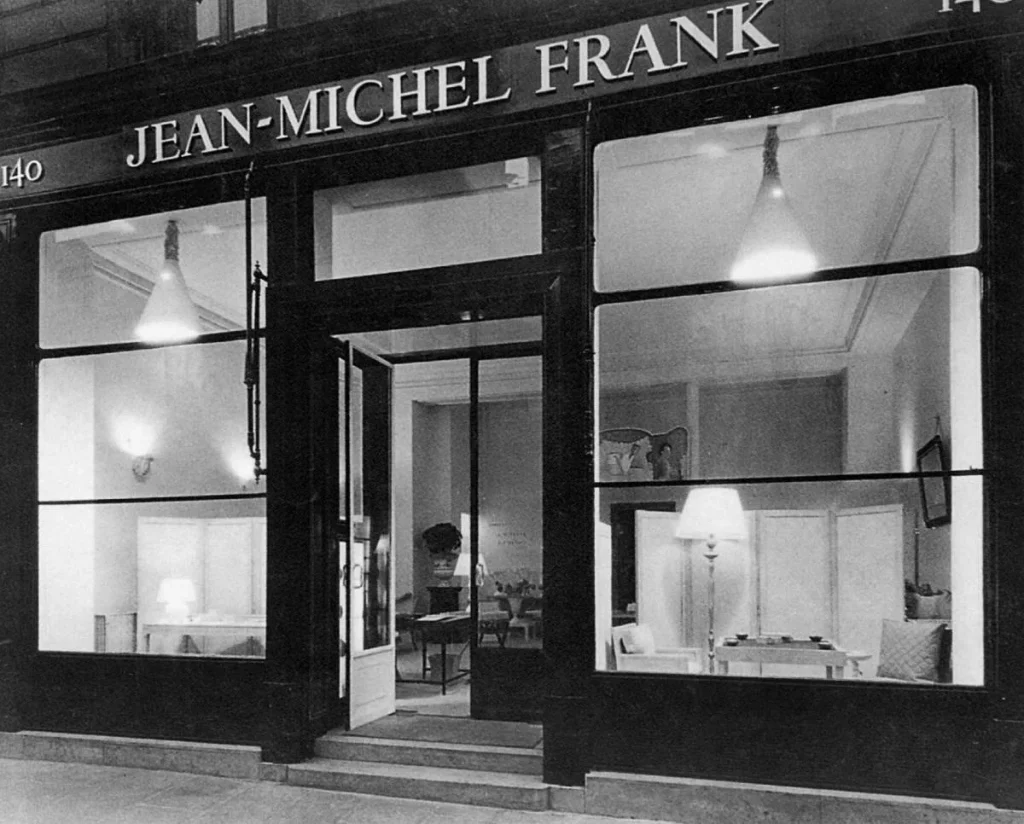

Some of the Frank images that I love the best are of his storeroom and shop on rue Faubourg St Honoré. More than the hallowed and stately rooms built for millionaires, his shop and workspaces project an immediacy and informality to the pieces arranged there. I could walk into those spaces and discover something for myself (how I have dreamed of just that!). Having a store/showroom gives the designer his own world to visually define and test ideas.

I grew up working in my fathers’ stores, later in the gallery I managed in Hong Kong and over the years I have built many stores in Thailand. Each new store is a re-imagining – a new world-in-microcosm that projects the ideas formed in the design studio and workshops. It is the face and theatre of the business where people can walk in and discover things that exist nowhere else – the polar opposite of a chain store. I imagine that Frank had the same excitement and enjoyment that I have in designing these gallery spaces and displaying and changing them as new designs arrived. During this long Covid period I have been designing a new space and it has brought a welcome escapism from the more prosaic business work. It will soon be open in Bangkok’s fascinating river district – the most interesting and vibrant part of the city.

Looking deeply at the work of Jean-Michel Frank, I have found a shared joy in the simplicity of form and the beauty of a palette of precious, natural materials. The creation of the pieces is an oasis of satisfying discovery – a communion with people and skills that is endlessly nourishing. It is this communion and balance of elements that enhances the creative process and takes it to a place that is beautiful for the maker and the beholder. Thank you Jean-Michel Frank for being a constant friend and wonderful influence as my own creative work evolves and deepens.