More than any other craft gilding is universal. It has been taken up across history and across the globe: first used 4,000 years ago in Ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia and the early dynasties of China, the civilizations that followed all adorned their kingdoms with gold leaf from the Ancient Greeks and Romans, to the Emperors of Japan, to the French kings of 17th century Versailles. In Ayutthaya, royal artisans applied delicate sheets of beaten gold to lacquered woodwork and the surfaces of Buddhist scriptures, cabinets, royal regalia – objects of divine and sacred significance. The Kingdoms of Siam embraced gilding not only as a way to venerate objects of importance but also to adorn architecture lavishing the spires of palaces and the stupas of temples with the delicate leaves of gold.

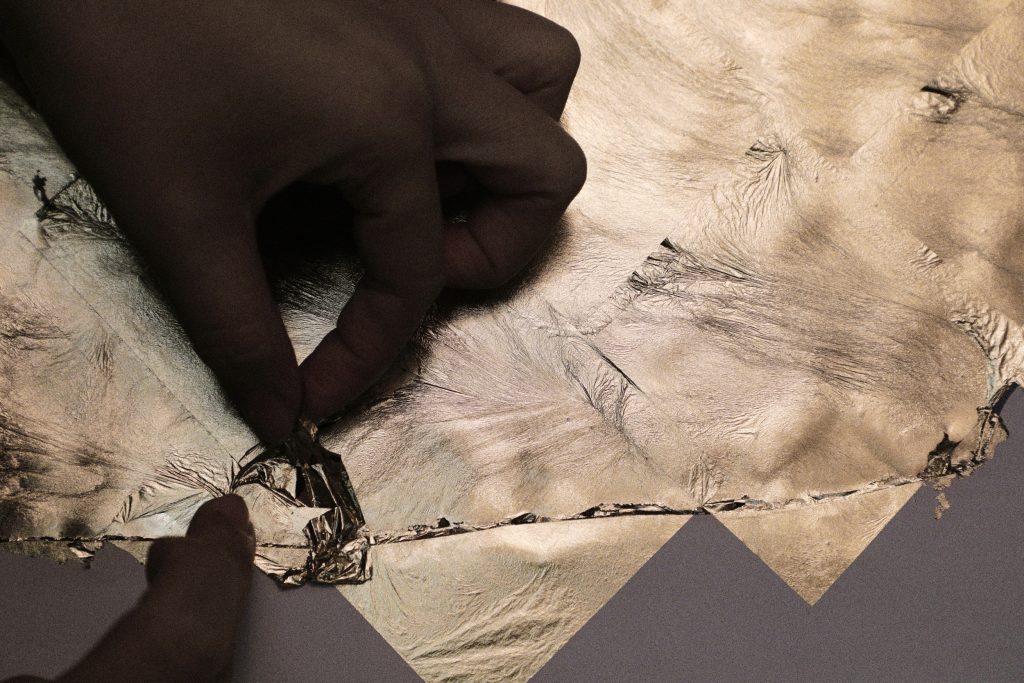

The making of gold leaf is a story of transformation through pressure. It begins with a pearl of solid gold placed between layers of vellum paper, the stack built up like a miniature geological core. Hammered in patient, repeating circles, the pearl spreads outward – thinner, wider, lighter with each strike. With the tremendous force of the hammer, subtle lines form in the sheet: sunburst striations radiating across the gold, like layers in the earth’s mantle compressed over time. Through this patient process, the metal becomes a sheet less than a micron thick — fragile, luminous, and ready to be laid onto a surface.

Gold can be seen as a lavish way to display prestige, but at Alexander Lamont there is a bid for a subtle golden touch, an accentuation of the craftsmanship beneath, a whisper of a soft golden core caressed by lampshade or sconce. A desire for a space to feel special is met, in sunlight falling upon a wall in cascades of gilded patterned straw marquetry or a fiery pupil blinking from within a darkened bronze iris.

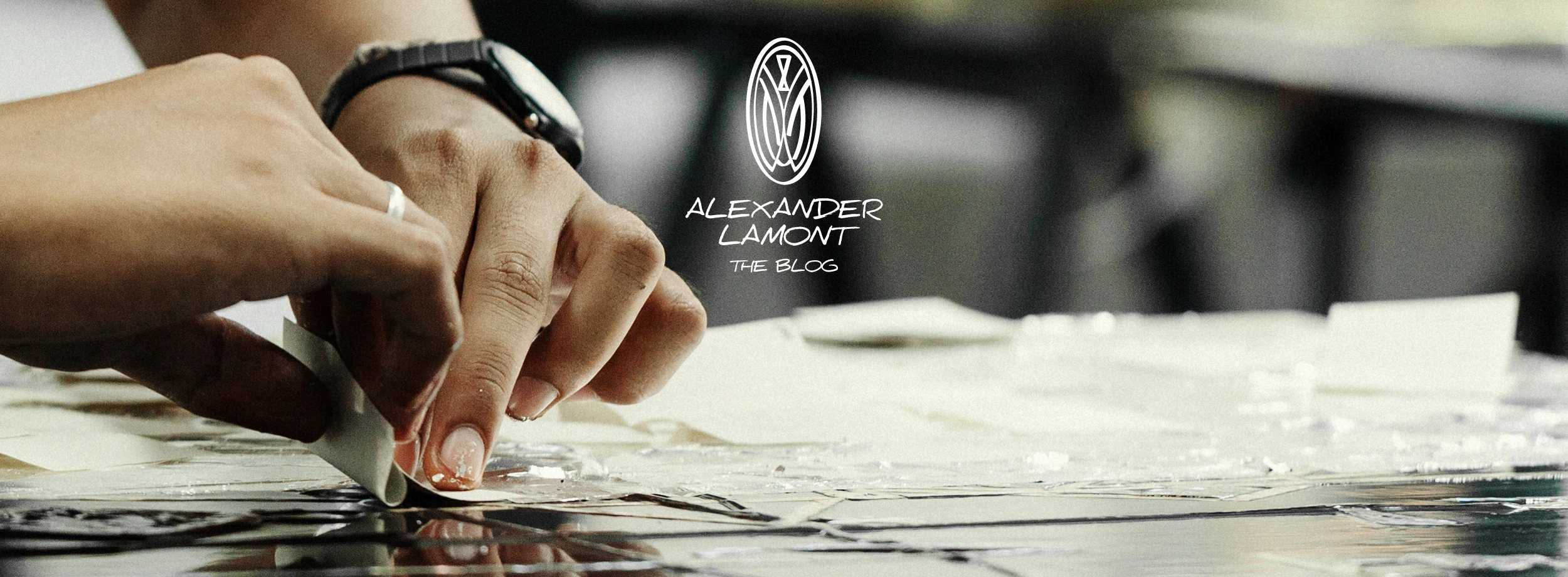

Gold is placed onto a surface by hand, pressed down by delicate fingers, and brushed away to reveal a new life infused with the material beneath, an afterglow. The gold is dusted away in flecks, almost excavated. The craft becomes an endeavour between artisan and object to bring light and reflection.

Coming upon darkening winter months and frostier evenings, the refuge of a cozy interior becomes ever more delicious when cast in the rich tones of gold leaf, met by the warmth of cast bronze, rich natural lacquer or tactile shagreen. The pleasures of this material can be tickled in the subtlest of encounters – a glint of warmth held in a dark lacquer inlay, a hue licking the curves of the Labellum sconce and the Hourglass sconce.

The sensual element of gold is brought to the surface in Alexander Lamont’s gilded creations, casting away the piercing winter cold, and inviting a furnace of sun into the home this holiday season.

Author : Lauren Lamont