This October marks the 40th anniversary of the passing of Eileen Gray (1878 – 1976) a most significant artist who navigated between Art Deco and Modern Architecture.

A movie The Price of Desire by Irish director Mary McGuckian (2015), a documentary Gray Matters by Marco Orsini (2014), a 2013 retrospective at Le Centre Pompidou along with the restoration of her modern architectural masterpiece, e.1027, has helped bring her legacy to the foreground in recent years, but Eileen Gray remains an enigmatic figure in the design world. For all she accomplished in her 98 years, it was the constant metamorphisis of her work and her modern independance that kept her interested, engaged and ultimately not pinned to a singular career. Painter, designer and architect she did it all.

Born to an aristocratic Irish family she moved to London in 1898 to study at the prestigious Slade School of Design. Walking on Dean Street in London, she chanced upon a lacquer sign for a workshop (D. Charles, a painter who specialized in lacquer repair) and she went inside. Enchanted by the Chinese and Japanese lacquer screens, she asked if she could work there and by the following week her first lacquer apprenticeship had begun.

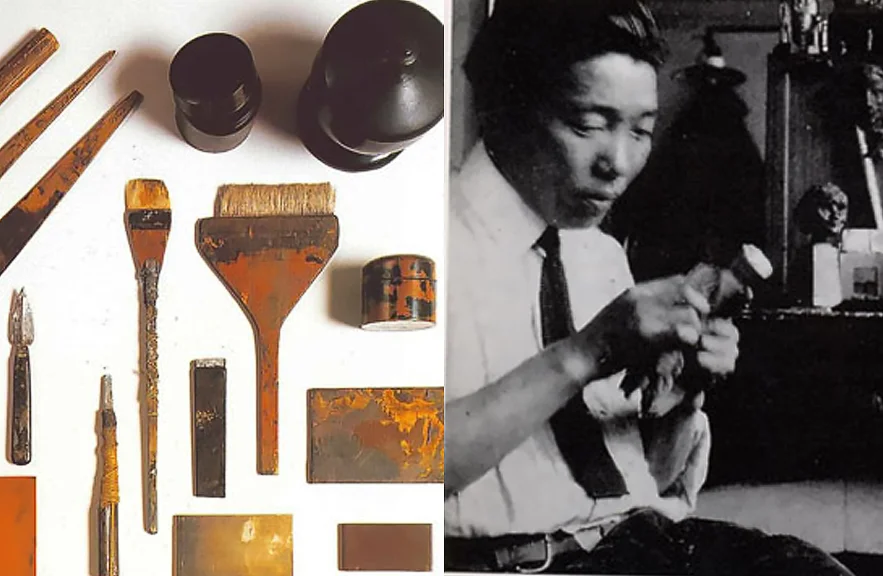

In 1906, Gray moved to Paris and began her career as an artist and painter. She found herself dissatisfied with just drawing; “Frankly, drawings were no use. I wanted to do something useful. So I started with relief screens and panels.” Through her contacts with Mr. Charles, she made an introduction to a young Japanese lacquer craftsman, Seizo Sugawara, from Jahoji in northern Japan, a place famous for its laquerware. Gray worked alongside him and his staff of French assistants for four years.

Not content to follow traditional methods, Gray began developing her lacquer work with striking colors and understated shapes. Her screens were abstract with clean lines and simple forms; quite the departure of the more traditional nature scenes and motifs. By 1913, she felt confident enough to exhibit her work – panels titled Le Destin, at the Salon des Artistes Décorateurs. The panels attracted the attention of couturier Jacques Doucet, who also commissioned other works of lacquer for his Paris apartment. Doucet insisted that she sign Le Destin and these were to be the only works that she ever signed.

World War I erupted and her work was interrupted. Gray became an ambulance driver for the French army in Paris but a surplus of drivers ensued and she returned to making lacquer: first in Paris and later in London. However, her clientele was in Paris and so she returned to the city and began working on an apartment project on Rue de Lota. She created dramatic lacquer panels and furniture to go alongside tribal art. She lined the walls with hundreds of small rectangular lacquered panels that would go on to be developed into one of her iconic works the ‘Block Screen.’ The apartment was hailed as a triumph of luxe modern living.

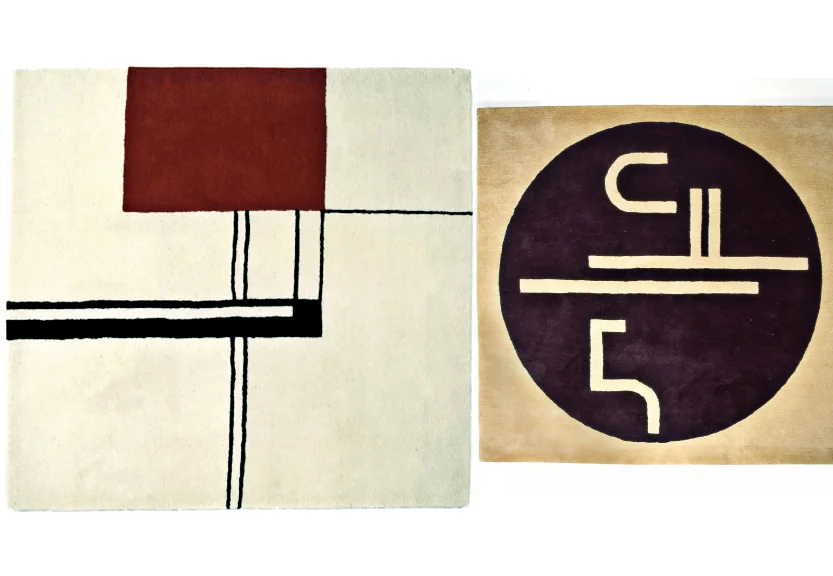

Encouraged by the success of the apartment she opened a shop in 1922 to showcase her work – Galerie Jean Dèsert. Selecting a fictional male name for her shop certainly addressed the times and modernity of her ways. The business did well and served as a space to exhibit her furniture, lacquer, carpets and some painting and sculptures. The shop enabled her to work together with friends such as Sugawara and weaver Evelyn Wyld, whose carpets were made with natural wool from the South of France and vegetable dyes.

Galerie Jean Dèsert began attracting the ‘beau monde’ in Paris, although Gray was never part of an arts & craft guild or organized salon. Through her work she met Romanian-born architect and magazine editor Jean Badovici, a close personal friend with whom she also worked. He suggested she try her hand at architecture and together they built a villa, e.1027, on a then isolated stretch of the French Riviera. Working on the design and construction of the home from 1926 to 1929 it also became the ultimate showroom for her more modernist later work. She became one of the first designers to work in chrome, preceeding Le Corbusier, Charlotte Perriand, Mies Van der Rohe and Marcel Breuer. Gray poured her heart and soul into the villa, designing with flexibility, movement and always an eye to the senses and practical demands of everyday living. Every detail was carefully considered, from a tea trolley with a cork surface to reduce the rattling of the teacups, little drawers in closets that pivoted outwards to reveal the inner contents, to balconies and movable windows that allowed for constant engagement with the wind, sun and sea. Le Corbusier was quoted as having said, ‘a house is a machine for living’ to which she famously rebutted, ‘a house is not a machine to live-in. It is the shell of man, his extension, his release, his spiritual emanation.’

After the war and throughout the rest of her life Gray continued to lead a quiet, reclusive life while continuing to design furniture and homes that always took into consideration the occupant’s psychological and spiritual needs. Her buildings went on to demonstrate a profound knowledge and understanding of space, the use of light and ingenious planning. She continued through life to find new solutions, to explore new materials and to most of all design for the people.

In 1968, a laudatory article by Joseph Rykwert in Domus magazine brought renewed attention. An exhibition of her architecture was organized in Graz and Vienna and in 1972 a Paris auction of Jacques Doucet’s apartment and an exhibition at the Royal Institute of British Architects in London added to the revived interest in her work. Later that year she worked with Zeev Aram to reproduce her designs which are still produced today and have become design icons. Never one to seek the limelight, Gray remarked to her biographer Peter Adam, discussing her ‘revival’ so late in life: ‘One must be grateful to all those people who bother to unearth us and at least to preserve some of our work. Otherwise it might have been destroyed like the rest.’

Sources:

Eileen Gray – Design and Architecture 1878-1976 by Philippe Garner published by TASCHEN

http://www.irishtimes.com/life-and-style/people/eileen-gray-thoroughly-m…