As the managing editor for the blog, I see many photographs every week of the current work going on in our workshops. I come across various images that capture my attention for different reasons but a recurring aspect is that of the tattoos on the hands and arms of our artisans. Every time I see such a photograph it brings me a sense of place; an immediate reminder that “yup, I’m in Thailand.” Even after six years in Thailand, the country is so familiar yet constantly surprising and although tattoos are quite commonplace nowadays, their context is very different in Thailand. Tattoos have a unique and rich tradition here and I would like to share with you a look at ‘sak yan’ or Thai sacred tattoos.

Research has shown that virtually every major society in the world has had some form of sacred tattoo culture, including Europe, Japan, the Americas, Africa, Polynesia and Oceania. In Joe Cummings in-depth and insightful book, Sacred Tattoos of Thailand, he quotes an Iban proverb in Borneo that says it best, “A man without tattoos is invisible to the gods.” Clearly, it’s only human to seek a little magic and help in protecting oneself from danger; be it evil spirits or man himself.

Cummings explains that the origins of sak yan (sak means“prick” or “jab,” as with a needle in Tai and has become the Thai word for tattoo. Yan is derived from the Pali-Sanskrit word yantra or geometric designs steeped with spiritual power) are not clear but the tradition is saturated with complex beliefs and traditions of nearby India and neighbouring Cambodia and includes their influence in Brahmanism, Buddhism and animism.

Temple paintings helped document the tradition by depicting Thai warriors wearing sak yan in murals dating back to the early 19th century. There is also evidence that Siamese soldiers from the Ayutthaya kingdom (14th to 18th century) wore jackets covered in yan but these were often lost in battle so they eventually began wearing the yan directly on their skin as tattoos. And up to half a century ago it was commonplace for many Lanna (northern Thai) and Tai Lu men (peoples from southern China and Northern Vietnam), to have tattoos from the waist to the knees to give them power for work, civil defense and to bolster their virility. Many men also wore tattoos on their chest, back and arms for blessings and good fortune. In fact, a man was considered “raw” or “undressed” if he didn’t have any tattoos.

However, the actual tattoos only tell one part of the tradition. To be truly called a sak yan it entails much more than body decoration. A magical blessing by a khru sak (tattoo master) is essential in order to allow the sak yan to work its magical power. When a master applies sak yan to a disciple, a code of conduct and the five Buddhist precepts are discussed and expected to be followed for the rest of their lives, in order to maintain the sacred power of the tattoo. The Buddhist precepts include: refraining from killing, stealing, lying, sexual misconduct and intoxication. Failure to comply causes sak yan to lose its power.

It also follows that every year the disciples have the opportunity to “recharge” their tattoos by paying respect to their tattoo masters during a ceremony. In essence, as Cummings states, “A proper respect for the tattoos, one’s master and one’s neighbours, along with an effort to remain mindful of one’s conduct in daily life, is considered of uppermost importance. Thus the tattoos are an aid to living a blessed life, but only if the disciple participates in the process.”

Yan on a glass door at Alexander Lamont workshop in Bangkok applied during the blessing of the workplace by Buddhist monks. “The script commonly used is a mixture of local and nonlocal script very often no longer used. Old Khmer script, Lanna script and the language the script spelt out is Pali, the canonical language of Theravada Buddhism. It is traditional to use non-native language as a way of calling upon superior magical powers and sorcery,” says Cummings.

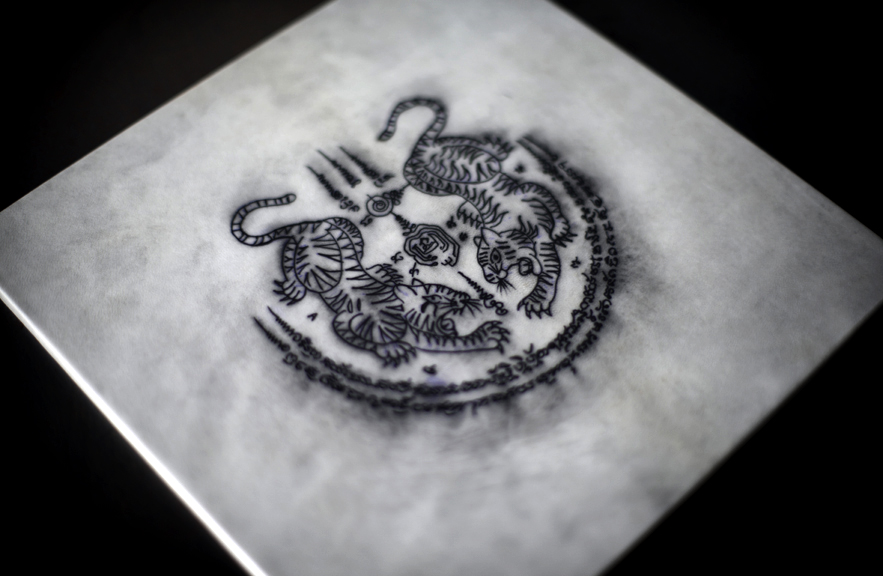

Yan is also commonly found on many other surfaces other than skin – squares of cloth, drawn onto the bonnet or interior roof of a car, often seen on taxis and painted above doorways to houses, schools and offices. Fascinated with the tradition and beauty of the script and craft, Alex has recently been experimenting with the process of applying a tattoo design on parchment. Imbued with tradition, art, symbolism and discipline, sak yan is yet another art form the Thai’s have enriched and made uniquely theirs.

Sak yan on parchment for Alexander Lamont. Sacred symbols are often used alongside yantra – lotus flower, the Satkona (similar to star of David) and the Hindu swastika symbol. Fearsome animals are also popular, Indian monkey god Hanuman, as do tigers, dragons, birds, snakes, lizards, hermits and eels.