I have pursued lacquer for decades: the fabled material that lies between East and West, Kyoto and Paris. It is to my eyes the most alluring, subtle yet iconic material, and the most difficult to use. It’s easy to see why Jean Dunand and Eileen Gray, two groundbreaking designers of the turn of last century, became fascinated by this material and asked Seizo Sugawara to teach them the mysterious secrets of its use. Liquid, dark, smokey, polished. Pigmented with the sort of natural ingredients that might have been brought to Europe by Marco Polo: cinnabar, cashew oils, pounded lapis, gold powder. Lacquer is a monastic material demanding patience and deliberation and more patience. During the Ayuthaya period, Thailand was a major centre of lacquerware, but alas no more. So in 2009 we began our first steps in working with lacquer, the sap of the lacquer tree.

These are the key things to know about working with lacquer:

- Source only the purest lacquer with minimal water content, because if you don’t you will experience a blindingly itchy rash over your hands and arms.

- Find a room which is very humid and has no dust: natural lacquer will only dry in humidity – that’s why Europe had to adapt the technique with all manner of alternatives such as shellac and other varnishes.

- Prepare the surface with incredible attention to detail. Any pimple in the surface will be magnified in the lacquer like ripples in a lake. We often create a base of four layers of gesso, each layer being sanded to a perfect ‘babies cheek’ smoothness before any lacquer is applied.

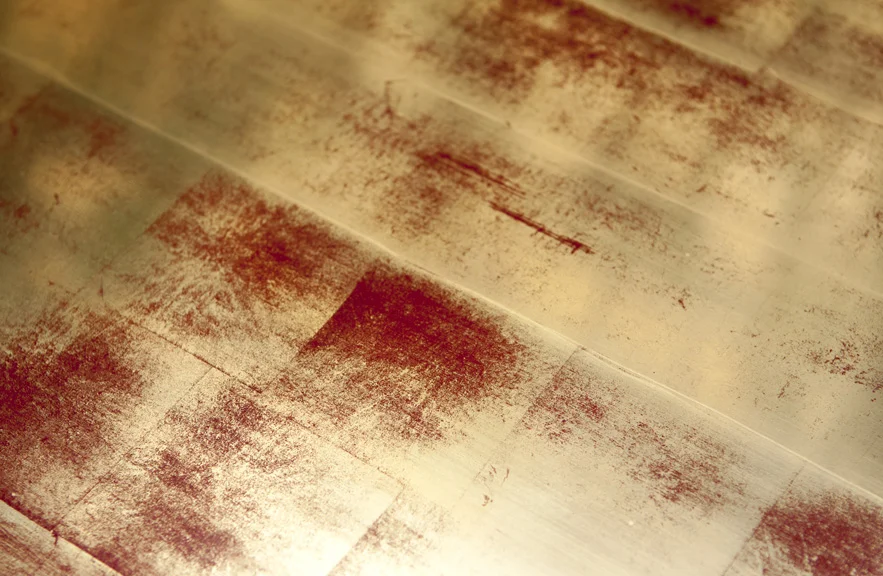

- Mix the lacquer with the pigments of your choice. Lacquer mixed with cashew oil creates the darkest, richest, most luscious chocolate-red imaginable. Cinnabar creates a brighter ‘Burmese’ red, and powdered oyster shell a silky ivory white. Of course, you need to have something rather beautiful upon which to apply the lacquer. We recently lacquered a box that was covered with stingray skins (nineteen to be exact). It sits on my desk–you can see the picture below–and all of my visitors, attracted by the glossy layered surface, reach out to touch it. The lacquer pools between the small enamel beads and stays low around the larger beads. It thins at the corners and edges. The movement of the lacquer is revealed by the object itself.

- Cover your object in layer after layer of lacquer until you are happy with the result. There is no ‘perfect’ number of layers. Each layer darkens the piece, deepening the tone, clarity and depth of the surface. The box had about seven layers.

- After each layer, wet-sand the surface until it is perfectly smooth.

- Polish the final layer with natural carbon and/or powdered deer horn.

The experience of working with lacquer is beautiful. It is a material that speaks to a certain way of living: monastic, slow, methodical, detailed, simple… It is strong and becomes more refined with age. Like still waters, it runs very deep.