The Arts and Crafts Movement of the late 1800s was born in Great Britain in response to the impact of the industrial revolution on society. The Movement highlighted the worsening of living conditions in industrial Britain, and the downgrading of workmanship and quality in manufacturing and the decorative arts. More than an aesthetic style it was a philosophical and political movement that sought to elevate the status and influence of the applied decorative arts and of the craftsmen and women who made them.

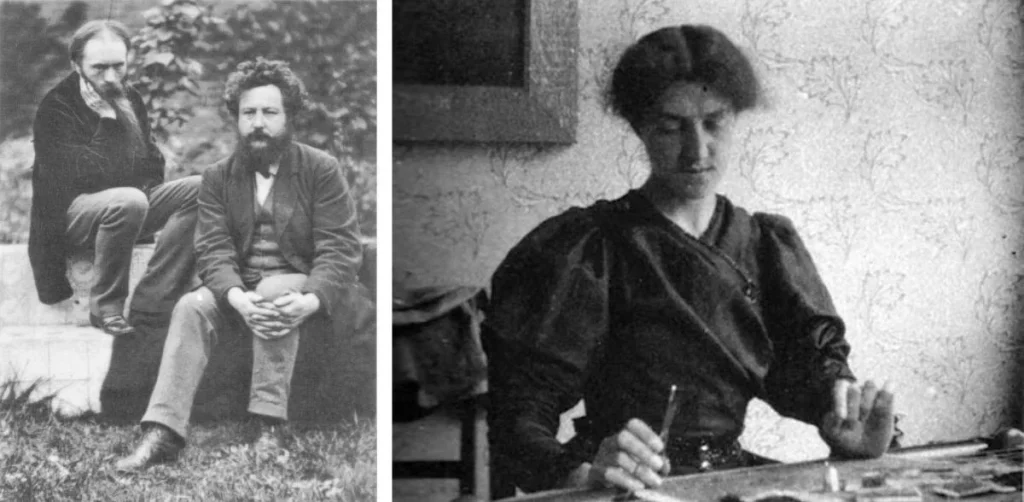

In today’s world there is a growing conversation about the role of design in our highly industrialised society, and the importance of sustainable materials, fine craftsmanship and form integrated with function. The roots of these design values and ideals can be traced back to the Arts and Crafts Movement of the mid-19th century, when a small group of creative, intellectual people began to question the industrialised approach to the manufacture of objects, seeing it as dehumanising, and leading to the subordination of environmental and social concerns, as well as aesthetic values and the integrity of hand work, to the economics of mass production. Architect Philip Webb, designer William Morris and his daughter May, poet and artist Dante Gabriel Rossetti and artist Edward Burne-Jones among many others were all associated with the movement.

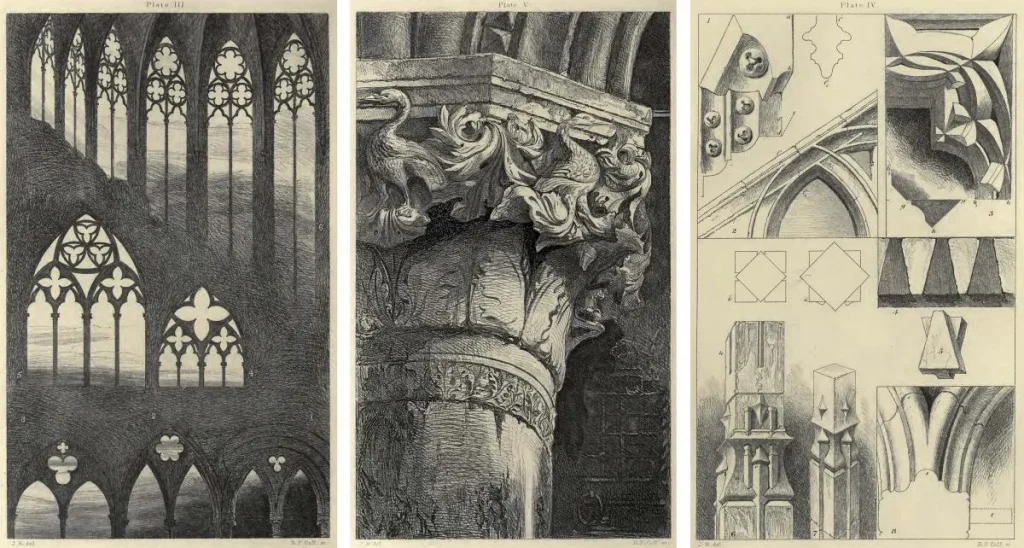

The influential art critic John Ruskin paved the way for the Movement in his writings about art, architecture and craftsmanship. Ruskin revered the craftsmanship of the Gothic period, its embrace of nature and natural forms and of the free artistic expression of artisans in constructing and decorating buildings of monumental importance. He saw in the Gothic ideals an organic connection between worker, guild, community, nature and God which provided a counterpoint to the rapidly changing world around him. Ruskin wholeheartedly rejected the new architecture of the Victorian era which relied instead on the soulless reproduction of classical motifs through mechanised work and standardised processes.

The Arts and Crafts Movement received its name from the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society, a group founded in 1887 in London whose principle aim was to promote the work of decorative artists. At its first exhibition in 1888 the Society showcased examples of work in the fields of ceramics, textiles, metalwork and furniture among others. These exhibitions became the most important public forum for the decorative arts and were critical in changing the way people looked at manufactured objects.

Probably the most influential figure of the Arts and Crafts Movement was the English poet and designer, William Morris whose aesthetic and social vision for the Movement grew out of the work he did with a group of fellow Oxford University students including Edward Burne-Jones. William Morris and his group were very much influenced by the writings of John Ruskin. They believed in the importance of creating beautiful, well-crafted useful objects for everyday life that were manufactured in a way that preserved the integrity and connection of the craftsman to his work and creation. Morris was not wholly opposed to the use of mechanization in production but he felt that the division of labour in the manufacture of an object led to the degradation of both the experience of the worker and the resulting product. Morris argued instead for the return to a system of manufacture through small scale artisans and workshops to provide for society’s needs.

In 1861, William Morris established the company, Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co making and retailing furnishings, textiles, wall coverings, stained glass and decorative arts with a medieval inspired aesthetic and with a respect for traditional craftsmanship. Through his work with the company William Morris soon became internationally renowned for his distinctive decorative designs for wallpaper and textiles. Many of these are still manufactured today under licence using Morris’s original printing blocks. The company not only mobilized collaborations between artists and painters, who would provide designs for skilled manufacturers to produce, it also achieved a commercial distribution through its own stores and stores such as Heal’s and Liberty’s allowing Arts and Crafts ideas and values to reach a much wider audience. The Arts and Crafts movement of Great Britain went on to drive a renewed interest in the decorative arts across the world. Its influences are found in the Art Nouveau movement in France, the Arts and Crafts Movement in North America and the folk art revival of the Mingei movement in Japan.

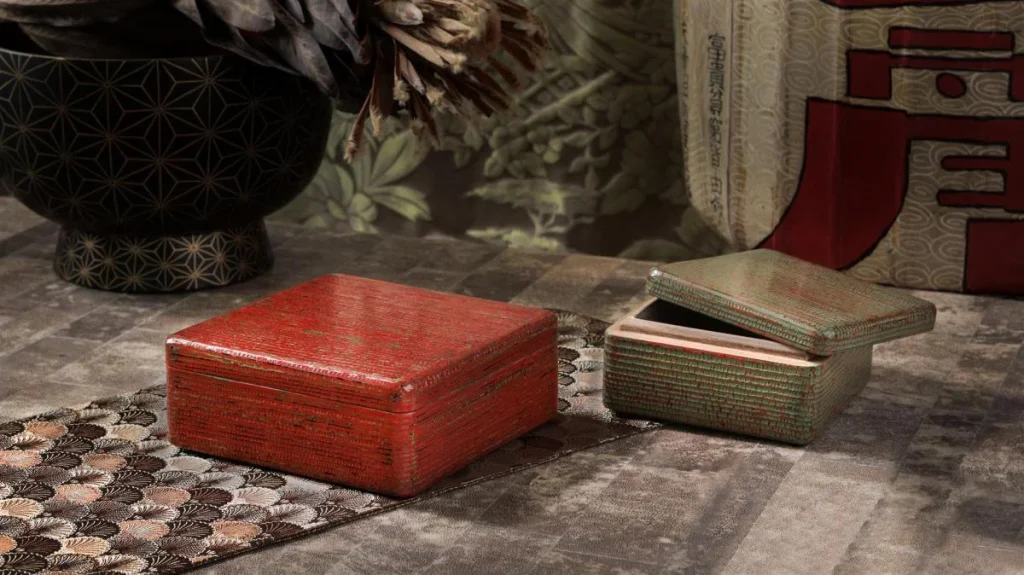

Though working within a very different aesthetic, Alexander Lamont shares many of the values of the Arts and Crafts Movement. Craftsmanship and the work of our artisans form an integral part of each one of our designs which emerge from an ongoing dialogue between designer and artisan in the exploration and innovation of our materials. Each piece is the expression of a journey from concept, form and material, through the detailed rituals of craft, to the end piece imbued with its own beauty and spirit.

Today the world faces a technological revolution, and the challenge of reversing the environmental damage of 200 years of industrialisation. The philosophy of the Arts and Crafts Movement remains as relevant and inspiring today as it did at its birth, as more and more people embrace the beauty of everyday objects made with natural materials and the work of human hand and eye.

“The past is not dead, it is living in us, and will be alive in the future which we are now helping to make” – William Morris