The art of lacquer is one of the alchemical and seemingly elusive techniques found in the decorative arts. It has its origins in early China and Japan and has produced works of exquisite refinement. From the most delicate articles of a courtesans vanity to the meditative perfection of tea utensils to armour and robust storage boxes, lacquer has been loved for its durability, tactility and flexibility as a material of creativity and for its depth of lustre and transcendant beauty in the eyes of those with a taste for such things.

To make things in lacquer requires an appreciation of colour, science and control that is applied in layers; with success or failure only revealed at the final polish. Drawn from a tree, natural lacquer has a translucency and character far superior to the plastic ‘lacquers’ that make up nearly all such finishes surrounding us today. The natural or vegetal lacquer we use is only worked in Asia, where the heat and humidity provide a perfect environment for the work.

The work of the lacquer artist lies in a strong understanding of the implications of each moments energies and how they will impact the finished result in many weeks time. A grain of dust grows tenfold if it is ignored in the sanding process and then covered with lacquer. A dimple caused by a spec of wax (wax repels lacquer) will grow layer by layer like a ripple affecting the surface. Thus the hand and eye work together to achieve a close perfection of smoothness before any subsequent layer can be applied.

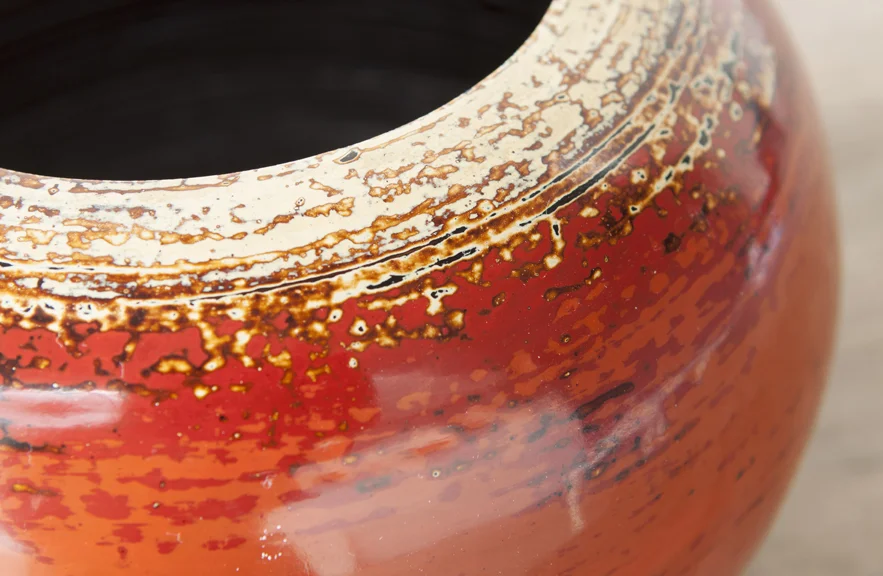

A bowl being developed showing 18 layers of lacquer pigmented with Japanese reds.

My interest in lacquer is partly metaphorical; a world is discovered within the depth and experience and hours of work. We go through our lives gaining experiences that add layers to us in different ways, like the rings on a tree. If the tree loses a limb or a hard knot grows, then new growth will cover the place, remembered yet gradually hidden beneath the surface. And with lacquer, there is a ritual to this process of burying yesterday’s discoveries either to hide them forever in smoothness or, in certain styles, to bury them only to expose them later through the polishing and sanding work like a trauma released, the result found to be unexpected and kind. The valleys and the hills of the cured lacquer are exposed like a contour map. This process therefore uniquely captures and contains artistically an expression of our humanity – a symbol of the experience and journey we have traveled.

A spun bamboo bowl we made whereby the uneven strips of bamboo are encouraged to gently impact the lacquer

Dramatic results can occur in lacquer work. As a connoisseur, occasional practitioner and passionate lover of this craft above all others, I find a strong tactile connection to these pieces that are conceived and built up so slowly. I see them evolve from simple forms into rich, sophisticated, individual pieces with all the layers of lacquer having brought them into mature beauty.

Natural lacquer, different from all those plastics, does not dry. In fact, if you took some Asian lacquer to the West it would likely sit in the relative cool and dryness and remain tacky for many months before dulling. In the heat and humidity of Asia, we have the perfect conditions for this material that cures rather than dries. A molecular change happens through contact with warm humidity (ideally 28 degrees C, 83 degrees F/70% humidity) that brings the particles into a new arrangement; an alignment that hardens and closes and that continues to harden over its life. Colours also change when pigments are added to the lacquer. Reds may start sharp and opaque but they deepen and bloom and intensify as they age, giving the impression of a natural glow within. Like me, lacquer blossoms and finds itself in the heat and humidity of Asia!

I have been working with a technique of honed black lacquer in Burma for some time whereby I create a velvety finish that is warm to the touch and somewhat soft. I apply this over forms of spun bamboo, ceramic, bronze, carved wood and basketry. Such substrates bring their own irregularities and imperfections that add to the sense that no two pieces are alike. Our Steamer Boxes for example are based on nature’s most perfect boxes; the oyster shell. Carved from solid teak we apply about 15 layers of black lacquer in increasing levels of refinement that eventually allow the lid and base to fit together nicely. The form has a voluptuous shape that seems sensually encased in black; a perfect place to keep your pearls!

Steamer Boxes come in two sizes.

Steamer Boxes – before and after.

Spinning a bamboo structure in Pagan, Burma before the lacquer application.

The Ripple Bowls are the same black but over baskets that we have made in the Shan State of northern Burma. The basket base brings an undulating, uneven form that gives real movement to the lacquer. Such forms need to be made by hand, as does the lacquer application itself. As the layers are added and sanded, the pressure and energy of the lacquer workers is transmitted into the material creating an effect of black water being very gently breathed upon.

In so many ways, lacquer is at the heart of our enterprise and is a metaphor for the journey of life.

Ripple Bowls – an uneven Burmese basket covered with about fifteen layers of lacquer

Ripple Bowls – before and after

A wide bowl covered with natural brown lacquer and silver leaf before being rubbed through to create this pattern.

A group of lacquer bowls with tonal variety.

Our famous featherlight gold-lined votives made using woven horse hair to create a super thin, strong and flexible form.

A lacquer low table with checked pattern created by sanding through layers.